Some of you might think that toilets, or the biological necessities that inspired them, are disgusting. Others might think they’re boring. But, oh, my friends – you are wrong.

Toilets, or other mechanisms for handling human waste, are important. Essential, even. And human “waste” is actually a valuable resource that we’ve been, well, flushing down the toilet.

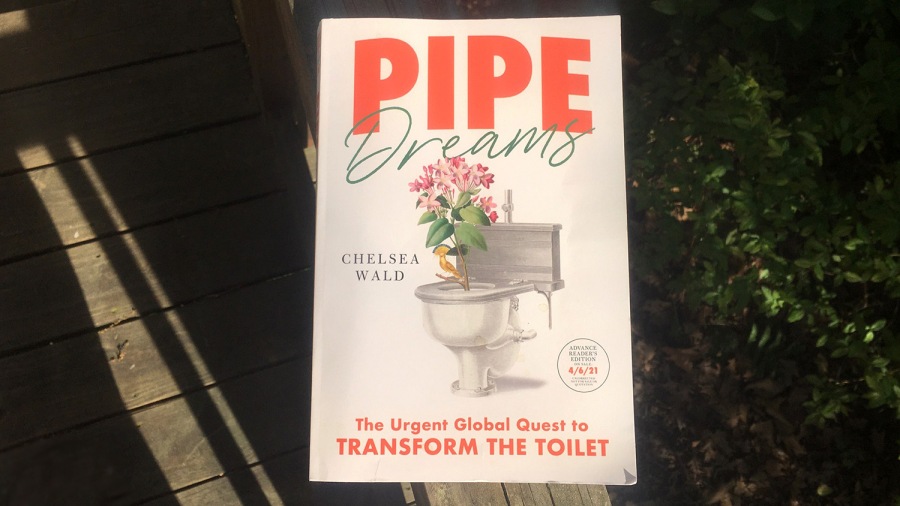

Chelsea Wald makes all of this clear very quickly in her new book, Pipe Dreams: The Urgent Global Quest to Transform the Toilet. The book spans centuries and continents, looking at the past, present and future of what humans do with their poop and pee. (And trust me, a lot of thought went into which words to use here.) The people, challenges and technologies she writes about can be inspiring, frustrating or humorous – but they are always fascinating.

I recently had the opportunity to ask her about the book, how she wrangled such an unwieldy subject (I mean, this is something humans have been dealing with for as long as there have been humans), and whether the work made her more tolerant of potty humor.

[Full disclosure: the book includes a reference to a researcher at NC State University, where I work. That’s not what drew me to the book (I find wastewater treatment issues interesting), but I thought I’d mention it.]

Science Communication Breakdown: This book answers a lot of the background-y type questions I often ask writers, so I find myself in the awkward position of asking you a question that I’m pretty sure I know the answer to. But folks reading this interview won’t know the answer, so I’ll ask it anyway. What made you start thinking about poop, pee and the future of toilets?

Chelsea Wald: I never had any particularly special relationship to toilets as a child or even much into adulthood. I didn’t have any intestinal disorders; I didn’t like potty humor. Nobody would have pegged me as someone who would write a book on the toilet when she grew up. But somehow I think that makes me a good messenger: I am here to tell you that literally everyone who pees and poops can – and should – care about this topic.

Like everyone, I have had some memorable encounters with toilets throughout my life–encounters that came to mean something more to me when I finally started putting it all together for this book. During my undergraduate education, for example, I felt frustrated by the relative dearth of women’s toilets in the physics building, which both reflected the composition of the faculty and students and also felt somehow prescriptive. During a fellowship at Toolik Field Station in Alaska, I came away with a strong memory of the overground toilet tanks, which collect all the pee and poop and truck it away so that the nutrients don’t contaminate the landscape, which is what scientists are trying to study.

But it wasn’t until 2013 that the book became a twinkle in my eye. That year, I wrote two very different stories that both had something to do with toilets: one was about innovative toilet concepts for low-resource contexts, and another touched on how we could harvest heat from city sewers. I felt that I had just skimmed the surface of something very deep and broad in the topic of sanitation, and I’ve been working on it since then.

SCB: At what point did you realize, “Holy crap, I’m going to end up writing an entire book about this”?

Wald: After those two 2013 stories, I let my curiosity take me in a lot of directions. I wrote about the ancient history of the toilet and the business of new types of treatment plants for fecal sludge (the goop that comes out of pit latrines). I had a lot of information but no framework that fit it all. I started writing a proposal for a book that was much more of a chronological history of the toilet, but that didn’t go well–the history of the toilet isn’t a straight line by any means, and I couldn’t quite figure out how to make a narrative out of it. I tried on quite a few other ideas over very long hikes with my husband in the hills of Vienna, where we lived at the time, before I settled on the future of the toilet as my topic. When I finally came up with the title – Pipe Dreams – I knew I was ready to finish the proposal and pitch it.

SCB: Did you have a clear idea of what the book would look like when you started out? A clear goal of what you were going to do?

Wald: Yes and no. The framing of the book – essentially, that we’re on the cusp of a new worldwide sanitary revolution that makes toilets better for our health, our environment, and our societies – stayed the same. So did my commitment to show that this is a problem that faces everyone on the planet by telling the stories of high-resource and low-resource areas as closely together as possible, rather than separating them, as is typical among experts and journalists (sometimes for good reasons). I also had a pretty clear idea of the subjects I would need to hit and several of the projects I would include.

But I had never written anything at this length before so I had to learn a lot on the job about how to organize many 10,000-word chapters into a book-length work. There was a lot of shuffling and screaming.

SCB: “Pipe Dreams” is about the past, present and future of how humans handle their excrement. Otherwise known as feces, waste, manure, crap or shit. Given the nature of the book, the word you choose to describe this substance is going to be used a lot. You settled on the terms poop and pee. What made you pick those terms?

Wald: Every writer on the topic seems to struggle with this. One doesn’t want to be too clinical or too crass. I don’t like “human waste” because one main point is that it’s not something we should waste. Fortunately, poop and poo have been gaining popularity in recent years (perhaps in part due to the poop emoji), and somehow no longer sound so goofy and childish as they once did, so I found it to be a relatively easy choice. And pee goes with poop. That said, I do mix it up a bit in the book just for variety, and when the context seems to call for it.

SCB: The book covers centuries of history, a rogue’s gallery of health and ecological challenges, a wide variety of historical and emerging technologies designed to address those challenges, and a host of obstacles to adopting the technologies. There is, in short, a lot going on. How did you go about organizing all of these pieces of information in order to create a clear narrative? How did you decide what order to put things in – and how to connect them?

Wald: At some point during my research I also had this very feeling – damn, there’s a lot here! The problem – and the pleasure – is that, since everybody poops, toilets are a window into just about every aspect of society. A book about toilets can be a book about everyone and everything. But most readers won’t have thought about it that way: I think most would start out with the assumption that the toilet couldn’t possibly be interesting enough to write a whole book about.

Rather than organizing chronologically or geographically, I decided to organize the chapters by some of what you might call the universal problems of toilets: (roughly speaking) health, infrastructure, liquids, solids, trash, inequality, and perception. Within each chapter, I try to give some relevant history and present status alongside the innovative solutions that might apply to various contexts, such as wealthy, poor, urban, and rural. Of course some themes, from the “ick factor” to cost, keep returning throughout the chapters, which I think is a plus because it underscores the interconnectedness of all of these problems and creates a bit of momentum.

In the end, I decided that, instead of trying to fully tame the impression of there being “a lot going on,” I would aim to leave readers as amazed as I have been by just how much there is to know about toilets.

SCB: This book introduces readers to a wide variety of interesting people, such as a man who intentionally infected himself with whipworms. Repeatedly. These people help to place the work you’re discussing into a human context – it’s more than a purely abstract concept. How do you find sources like that?

Wald: For this book, I focused on looking for innovations or solutions that I wanted to highlight: projects, designs, technologies, approaches. I searched quite widely, attending conferences, reading books and news articles, listening to podcasts, taking online courses, and otherwise just poking around the internet. When an intriguing concept came paired with an interesting human story, I tried to bring that out, because I think that, in the end, this is a book about the odd and intimate connection between our species and this really specific technology that we use several times a day but rarely think about.

SCB: Given how squeamish some people can be when it comes to discussing excrement, did you ever have trouble convincing people to talk with you on the record? If so, how did you handle that?

Wald: This wasn’t really a problem, in fact. There’s a frank and open conversation going on in the world right now about peeing, pooping, and toilets, and I was just able to tap into that.

I think it’s also helpful in some cases that I’m willing to so closely associate myself with the toilet, so I clearly don’t think that it’s shameful. I mean, my book has my name next to a toilet on the front! And, in the book, I tell personal stories that are perhaps a bit taboo – for example, about how hard it was to take a shit after giving birth.

That said, when I was traveling – in Haiti, for example – some people didn’t agree to let me into their homes to see their toilets, but that was fine, since other people did. I didn’t need or want to pressure anybody who was uncomfortable.

SCB: You talk about some wonderful technologies and systems that effectively treat human waste like a valuable resource – which is amazing. But there are also a lot of challenges – a lack of funding, a widespread resistance to change, etc. Is there one challenge that stands out to you more than the others as the most formidable obstacle to implementing real change in terms of how we deal with our poop?

Wald: I’ve found that many people in the field feel frustrated that pilot and demonstration projects get stuck at that stage, despite the fact that they may have been successful. I think that it happens for a lot of reasons, ranging, as you say, from funding shortages for research and infrastructure to a resistance to change among potential users, political leaders, and industry professionals. In fact, I’ve learned this the hard way myself: Successful-seeming projects that I’ve highlighted in past stories have had to shut down or have suffered severe setbacks within just months of publication. There’s often not a single, simple explanation but instead has to do with multiple factors within the specific context of the project.

In short, nobody seems to have cracked the code on how to get new toilet concepts to scale in the way that the Victorians did during the sanitary revolution. And it might be that nothing will get quite to that scale, but instead the future will bring more of a patchwork quilt of good solutions that suit each context–and, one hopes, reach more people.

SCB: Are you more optimistic now than you were before you started working on this book? Or are you more worried?

Wald: This varies day to day. But I have to say that the pandemic has given me a new sense of urgency and concern around the various looming crises related to our toilet systems that I identify in the book, from the rise of antibiotic-resistant pathogens to the decline of phosphorus to the failure of wastewater systems due to extreme droughts and floods. Before, many of these seemed like the kind of events that could happen but rarely did, and certainly not in places where I live. Now they appear to me more like inevitabilities. So, in that sense, I’m more worried.

On the other hand, I think we’re seeing the public gain a new appreciation for government spending, which is a key element for shoring up and transforming our toilet systems. I just hope that the people and places with the fewest resources don’t get left out. They’ve lived without safe sanitation for far too long and should be the priority.

SCB: After spending all of this time thinking about what we can do with human waste, do you have a favorite technology?

Wald: Right now I’m kind of obsessed with urine diversion – that is, keeping urine apart for reuse. It’s a low-tech solution that’s workable almost anywhere. People have been trying to get it off the ground for decades but I think that the time might have finally arrived.

SCB: Writing a book is a significant undertaking, and time spent working on a book is often time not spent working on articles or other projects that pay in the near term. One of the questions I’ve heard a lot is “How do people afford to write a book?” So…how did you afford to write a book? How did you juggle book writing with freelance work? Did you get an advance that was enough to make ends meet? Were you able to secure fellowships or grants that helped subsidize the work?

Wald: This is a good question. My personal circumstances made this worthwhile for a few reasons. I have a partner with a steady income, so we can rely on his job to make ends meet. My freelance business was never lucrative, so my advance was a win. And I had already gotten a major travel grant from the European Journalism Centre for a related project on reclaiming organic (food, agricultural, and toilet) waste for agriculture, so I was able to piggyback my reporting for the book onto that.

On the other hand, taking on a book project at this moment in my life was particularly expensive, since I had just had a baby when I signed the contract. That meant that my husband and child traveled with me to many of the destinations on our own dime, and I had to pay for a load more childcare than I had expected so that I could do the reporting and writing.

Does the math work out for this project, at least so far? Probably, but I can’t say for sure.

SCB: I have one last question, and it’s something that I kept wondering as I read the book. A lot of humor revolves around poop and farts and pee and toilets. You spent hundreds of hours having serious, detailed conversations with people about poop and farts and pee and toilets. Did that make scatological humor funnier to you? Or less funny? What about the experts you talked to? Did they find this sort of humor amusing? Or is it the sort of thing that would make them roll their eyes?

Wald: I think it made it funnier! That may be because I had never spent any effort on refining my scatological humor, and, once I did, I found that I enjoyed it in the same way I would enjoy any other kind of writing prompt. The experts, while deadly serious when appropriate, tend to be really funny, too–or at least try to be. I’m on a group chat of sanitation experts, and they send around cheesy memes and jokes. Recently, it was a photo of a septic truck called the “stool bus,” which was painted as a yellow school bus with smiley poop instead of children in the windows. That said, my favorite jokes are the (at least seemingly) accidental puns and double entendres that just pop out spontaneously while writing or speaking. I still couldn’t trade poop jokes with a five-year-old. (Though I have tried to memorize a science-writerly standby if asked: Q. What do you get when a tree goes poop? A. A No. 2 pencil.)